IBRI Research Report #53 (2003)

GEOLOGY BEFORE DARWIN:

The Struggle to Find and Defend the Truth

about the Earth’s Past

David C. Bossard

117 Storrs Hill Road

Lebanon, New Hampshire 03766

Copyright © 2003 by David C, Bossard. All rights reserved.

ABSTRACT

The Golden age of geology bloomed in the

decades

just prior to Darwin’s 1859 Origin of the Species. Geologists

could

read for the first time the details of how God created a place for

mankind.

Opposition came both from religious leaders and from secular opponents

who saw their cherished notions challenged. The opposition was answered

by painstakingly careful argument, which by the time of Darwin was seen

by some prominent geologists to give strong evidence of God’s hand at

work.

After Darwin, though, this evidence in favor of a creator largely

vanished

from mainstream geology. In this talk we will discuss the state of

geology

just prior to Darwin and then ask whether the conclusions reached at

that

time were valid and why they disappeared from the literature after 1859.

EDITOR'S NOTE

| Although the author is in agreement with the doctrinal

statement of

IBRI, it does not follow that all of the viewpoints espoused in this

paper

represent official positions of IBRI. Since one of the purposes of the

IBRI report series is to serve as a preprint forum, it is possible that

the author has revised some aspects of this work since it was first

written. |

Geology Before Darwin:

The Struggle to Find and Defend the Truth

about the Earth’s Past

“I must confess that I was at first startled and alarmed by

rumours of changes and discoveries which, I was told, were to overturn

at once the science of geology as hitherto received, and all the

evidences

which had been drawn from it in favour of revealed religion. Though

well

persuaded that at all times, and by the most unexpected methods, the

Most

High is able to assert Himself, the proneness of man to make use of

every

unoccupied position in order to maintain his independence of his Maker

seemed about to gain new vigour by acquiring a fresh vantage-ground.

The

old cry of the eternity of matter, and the 'all things remain as they

were

from the beginning until now,' rung in my ears. God with us, in

the world of science henceforth to be no more! The very evidences of

His

being seemed about to be removed into a more distant and dimmer region,

and a dreary swamp of infidelity spread onwards and backwards

throughout

the past eternity.”

This quote, which comes from the preface to Hugh Miller’s Sketchbook

of Popular geology, sets the scene for our discussion. The

statement

comes just 10 years after the 1859 appearance of Darwin’s Origin of

Species. Already in that short time, the mood of geology had

shifted

dramatically from a wide concensus that noted strong evidence for God’s

handiwork in creation, to a naturalistic view that saw no need for God

— as Lydia Miller wrote, “God with us to be no more.” The dreary

swamp of infidelity seemed to flood the landscape, so soon after many

prominent

scientists had declared that the evidence of geology strongly points to

the work of a creator.

Lydia expressed the consternation that must have been shared by many

of these geologists: had new changes and discoveries indeed so altered

the landscape? What had they missed in their so-careful analysis of

geological

data — done, by the way, amidst hostile opposition from all sides, and

thus carefully, carefully crafted (or so they thought)? In the end,

Lydia

remarked that, no, they had not missed the mark; the evidence is still

the same; it has not changed: it is only being ignored and brushed

away.

So, with these words our task is set before us: to look at what

these

early geologists found, or thought they found, assess it, and then ask

again with Lydia Miller, “Is the evidence in favor of revealed religion

still the same? Is it still valid? And is it being brushed away to ‘a

more

distant and dimmer region’?”

To begin, I would like to say something about how I became

interested

in 19th century geology.

Over the past few years, I prepared a series of seven lectures on

the

theme, “What is Life?” The series ends with some comments about

geology,

and in my reading, I repeatedly came across references to Sir Charles

Lyell

(1797-1875), a prominent geologist in the mid-1800s. So I looked at his

two principle works, the Principles and the Elements of

Geology,

published in many editions between 1832 and the 1860s. As I read, I

marvelled

at the very positive way that the essential role of a Creator figured

in

his treatment. It was presented as a very natural conclusion of the

objective

findings of geology.

This caused me to wonder whether the recognition was pecular to

Lyell,

or whether it was pervasive throughout geology at this time. So I read

a number of other prominent geology books by other geologists of the

period.

Many of these authors had a similar theme that the geological evidence

points to a necessary role for divine providence. Some were more

outspoken

about this, some of whom wrote entire books on Natural Theology,2

but all wrote in a way that at least left ample room for, and indeed

argued

the necessity, of God in the creation process.

This positive theme about the role of a creator, sounded strange,

since

I had become accustomed to the naturalistic bent that is common in such

treatments today, and so it roused my curiousity: what had happened to

geology between then and now? Was the presumed creator’s role just a

gratuitous

addition in those old texts — perhaps a sop to the religious influences

which at that time still held sway in academia — or was it a

scientifically-based

conclusion?

The change, as we remarked, came with the publication of Darwin’s Origin

of Species in 1859. After its appearance, and the fervent promotion

by such spokesmen as Thomas Huxley and Ernst Haeckel, (adding to the

voices

of some earlier proponents such as Lamarck and Voltaire) a purely

naturalistic

development of geology, leaving out any mention or admission of a

Creator,

became the required standard for a “scientific” understanding of

geology.

So we will begin with a brief review of the state of 19th century

geology

up to the time of Darwin, and some of the findings that spoke in favor

of a creator. Then we will try to understand what happened after the

appearance

of Origins.

The Golden Age of Geology. The first half of the 19th century

was the golden age of geology. Much of the modern terminology, and the

outline of the geological history of the earth were laid out at that

time.

I think it is hard, looking at things from our modern perspective,

to

appreciate how unexpected it was that the Earth would preserve in its

own

rocks, a vast and minutely detailed record of its own past. Speculation

about origins was thought to be the province of philosophers and

theologians,

not scientists.

In 1802, William Paley (1743-1805) published his famous work

Natural

Theology, in which he used the details of nature, and particularly

of human anatomy, to show “the necessity of an intelligent designing

mind”

in creation. His book apparently caused quite a commotion, both

positive

and negative, and still excites comment 200 years after its first

appearance.

The book was written just before the science of geology

began

to take off, and the irony is that the very first sentence in Paley’s

book

shows how completely ignorant he, and most scientists of the time, were

of the vast store of information contained in the earth’s rocks. He

began

-- Chapter 1, first sentence of his Natural Theology --

“In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone,

and were asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer,

that, for any thing I knew to the contrary, it had lain there for ever;

nor would it perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer.

But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground…."3

Thirty years later, William Buckland4,

an early geologist, quoted Paley’s remark, followed by “Nay, says the

geologist,…”

and then goes on to tell what that stone may tell us, as detailed and

intricate

a tale as the one told us by Paley’s watch.

Important preliminary steps had taken place about 50 years earlier

by

Buffon (1707-1778) and Linnæus (1707-1778). Linnæus’ great

work on the systematic description of plants and animals, Systema

Naturae,

was published in many editions. He worked on this throughout his life.

The 10th Edition, published in 1758, established the practice, still

followed

today, of naming a species by two Latin names: the genus with an intial

capital, followed by the species, for example Homo sapiens.5

He firmly believed that species could vary only within certain limits.

At the same time, his contemporary, Buffon, worked on the 44 volume Historie

Naturelle, a vast attempt to catalog and describe all of nature.

These

early efforts to study nature systematically, provided an essential

basis

for the later systematic development of geology. In a sense, geology

could

not have proceeded without the work of these great men.

Modern geology began in 1799, some decades after the works of Buffon

and Linnæus appeared. In this year, it was first publically

recognized

that rocks preserve a detailed record of the Earth’s ancient history,

one

that is consistent worldwide. The sheer extent and detail of this story

told by the rocks was a total surprise to the scholars of the day, and

remains a surprise even today. Not that they lacked notions about the

earth’s

past in those days; Buffon’s work included much along these lines, but

those notions were mostly based on philosophical considerations rather

than on systematic, objective science.

No scientist or philosopher was prepared for the sheer volume of

significant

information that these rocks would tell — an example of the “silent”

voice

of Psalm 19, declaring God’s glory.

There is a little story about this beginning which can be named to

the

specific day, June 11, 1799. William Smith (1769-1839)6

was a self-educated engineer who worked in the quarries, mines and

canals

in Wales and England. In his work he became intimately acquainted with

the many strata of rock that exist on the Earth’s surface, and came to

realize over some years, that the strata are consistent all over

England,

that they are uniquely identifiable by the type of rock and the

fossils

that they contained, and that the strata were laid down in an

orderly

sequence from the very earliest, fossil-free strata to the most recent

strata.

He recognized that the strata in England and Wales tilt uniformly to

the South-East at about a 3° angle of tilt, so that the rock

outcroppings

generally become older — that is, lower in the sequence — as one goes

from

the vicinity of London in the south-east and on through Wales and

Scotland.

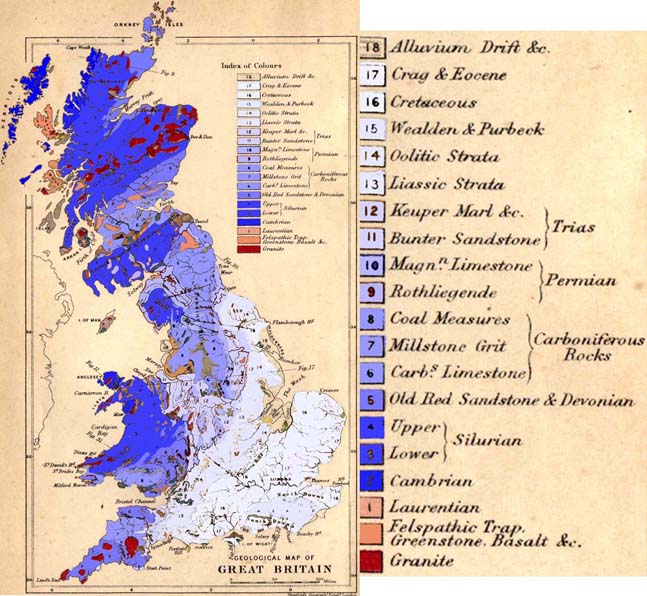

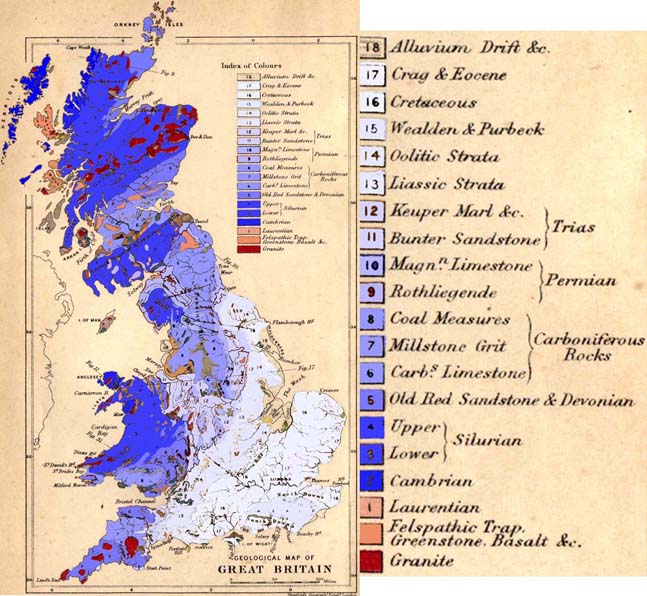

This ageing is shown in the geological map of Figure 1, where the color

darkens as the surface formation becomes older.

In Great Britain, the oldest fossil-bearing formations, occur in

north-west

Wales and Scotland and are from the Cambrian era. The youngest occur in

south-east England are from the Triassic period, shortly after the age

of dinosaurs. The K-T boundary which marked the end of the dinosaur

age,

is a line oriented in the north-easterly direction that passes about 20

miles north-west of London.

Figure 1

Geological Strata in Great Britain

(1878 Map)7

Note: Surface Fossil-bearing Strata indicated in Blue (Darker =

older

[lower]).

There is a story8

that William Smith visited two fossil collector acquaintances, Benjamin

Richardson and Joseph Townsend, on June 11, 1799, and during their

conversation,

he stated that he could give the particular stratum where their fossils

had been found, and also could predict what fossils would be found at

any

given location on the horizon about the home. They then trooped out

into

the surrounding countryside, and the accuracy of his assertions was so

astounding that the collectors urged him to list and identify the rock

strata in their proper order.

With William Smith dictating and Joseph Townsend transcribing, the

world’s

first orderly list of 23 separate strata with their thickness,

identifying

characteristics, and characteristic fossils, was set down on paper.10

Following the publication of this list, the same strata occurring in

the same order were identified throughout Europe, North America and

Russia.

Many of the modern names for the rock formations are the same names

given

to them by William Smith, which are often rather barbaric, as he liked

to use the names that the miners and quarrymen used.9

William Smith’s crowning achievement was a 6’x8’ geological map of

England

and Wales, based on data collected by himself , and completed in 1816.

It still hangs in the Burlington House in London.11

The key discoveries in William Smith’s work, recorded on that birth

day of geology, were,

• First, that most of the rock on land is sedimentary rock, laid down

in identifiable layers or strata;

• Second, that the strata extend over large areas;

• Third, that the strata are characterized by the type of rock and

fossil species; and

• Fourth, that the strata are laid down in a specific order.

The fossils are the key, and that is the peculiar insight of William

Smith. Before his insight, fossils were thought to be scattered about

more

or less by chance.

Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), the outstanding French Geologist of the

time, pointed out the significance of these fossils in his 1825 book, The

Revolutions of the Earth:

“How was it overlooked that it is to fossils alone that must be

attributed

the birth of the theory of the earth; that, without them we could never

have surmised that there were successive epochs in the formation of the

globe, and a series of different operations? Indeed, they alone prove

that

the globe has not always had the same crust, by the certainty of the

fact

that they must have existed at the surface before they were buried in

the

depths where they are now found. … If there were only formations

without

fossils, no one could prove that these formations were not

simultaneously

produced.12

Without the fossils, Cuvier continues, the science of geology would

never have begun. He made further points which may be summarized as

follows:

• Fossils tell us that many of the sedimentary rocks were

deposited in

situ under water -- not madly churned or rushing water but

tranquil

water, quiet water.

• Fossils tell us that the nature of the water and environment

changed

from time to time — salt water, brackish water, fresh water; deep

water,

shallow water; tropical, temperate or frigid water.

• Fossils tell us that these submerged sediments were subsequently

exposed

on dry land.

• Fossils tell us that the land was alternately submerged and

exposed

multiple times.

The publication of William Smith’s findings, led to a concentrated

effort

to interpret the geological record. Major efforts to catalog the

geological

formations arose worldwide over the next decades. One of the most

astonishing

of these efforts is the project to record the Natural History of New

York,

which was carried out over 50 years between 1843 and 1894, and directed

by a single person, James Hall, over that entire period.

The situation after William Smith’s discovery in 1799 was something

like walking into an Egyptian temple with hieroglyphics on the walls,

realizing

that the hieroglyphics were more than just pictures — they clearly say

something — and then puzzling out what they say (Figure 2). William

Smith

showed that the rock strata say something: they exist in an orderly

sequence,

they are of identifiable mineral composition and contain unique

fossils.

The question is, what do the strata say? The speech is there, but what

does it say? The answer to this question is the essence of geology as

it

developed by the mid-1800s.

Figure 2

Egyptian Hieroglyphics from the Rosetta Stone

It’s Writing ... but What does it say?

To begin with, the following general facts were already well-known

by

the early 1800s:

1. That much of the rock in the world

exists

in strata, which appear as if they were formed from sediment layer on

layer.

- Some strata are thousands of feet thick. The sum of

all strata amounts

to tens of thousands of feet of sediment.

- The strata occur in an orderly sequence that persists

worldwide, as far

as it could be checked at the time.

- Many strata — tens of thousands of feet thick in some

places — show

that

they were deposited under tranquil conditions, thousands of thin layers

laid in succession, sometimes showing evidence of tranquility such as

wave

ripples and impressions of animal footprints. 13,14

2. That almost everywhere -- even on the high

mountains

-- are extensive fossils of sea shells and other marine animals that

imply

that virtually all the land was once under water.

- In some localities alternating strata exhibit marine and land

fossils

indicating

multiple, long-lasting periods of inundation and exposure. (Example:

the

Paris Basin, studied by Cuvier)

3. That “modern” fossils occur only in the

uppermost

strata, while the lowest strata contain no fossils.

Each stratum corresponds to a geological age, and the

order of

strata progresses

from ancient to modern.

Every major kind of plant or animal has an identifiable stratum

where

that

kind first appears in the fossil record.

Once a kind appears, it is normally present in

later strata,

but each stratum

exhibits unique species.

The first appearances display a progression from simpler to

more

complex

plants and animals, culminating with mammals and humans.

Hitchcock observes: “The remains of animals and plants found in the

earth

are not mingled confusedly together, but are found arranged, for the

most

part, in as much order as the drawers of a well-regulated cabinet. In

general,

they appear to have lived or died on or near the spots where they are

now

found.”15

4. That the rugged landscape seems to imply a past

time

of violent land movements.

The facts that underlie these points can hardly be disputed by a

person

who has studied the evidence. The question is, what can one conclude

from

them?

One of Lyell’s major achievements concerned the last point. In a

word,

he argued that the implication of an extraordinarily violent past is

wrong,

or at least misleading. He devoted a major portion of his first book on

the Principles of Geology, to defend a uniformitarian view,

that the same laws of chemistry and physics prevailed in the past as

they

do at present, and (therefore) that the earth’s past can be fully

understood

by examining the present. There is no need to postulate special

conditions

or novel laws to explain what we observe in the geological record.16

He asserts,

“We come to no spot, in the history of the rocks, in which a system

different from that which now prevails appears to have existed.”17

A necessary implication of Lyell’s uniformitarian argument is that

the

rugged landscape formed over many thousands or millions of years.

The uniformitarian principle is also fundamental to modern research

into the behavior of the very early universe, as early as fractions of

a second after the big bang; the laws of nuclear physics and chemistry

are the same, if they are adjusted to reflect the high heat and density

that prevailed at that time: that is why we can use high energy

particle

accelerators to learn how particles behaved at those early moments.

Lyell gave convincing proof that the lifting of the land and the

upheavals

that produced the mountains occurred over very long periods of time,

and

came about so gradually that they did not substantially disrupt the

existing

ecosystem; in fact, viewed from the eyes of a contemporary observer,

the

up-lifting might go virtually un-noticed. Lyell noted, for example,

that

a 100 mile length of the coast of Chili rose about 3 feet in a single

earthquake

which, while it was violent in spots, did not substantially upset the

pace

of life as a whole.

Lyell concluded, after extensive research, that the rough terrain is

the result of vast movements of the earth’s surface, and that these

movements

were energized by heat deep in the earth’s interior. Once this view was

generally accepted, the question arose, where does the heat come from?

This proved to be very hard to answer, and indeed could not have been

answered

using the laws of physics and chemistry known at that time. The full

answer

didn’t come until over a century later, in the mid 1900s when the

science

of nuclear physics matured.18

It is a remarkable testimony to the dogged adherence of these early

geologists

to the factual evidence that they persisted in the view that heat from

the earth's interior is the primary engine for change over the geologic

ages, despite the lack of a plausible explanation for its source.

Opposition…

From the very first, as the geologists began to interpret these

facts,

there was vigorous opposition to their work. This opposition came from

all sides — from theologians on the one hand, to naturalists on the

other.

It seems that everyone had a reason to object to the young science as

it

was being developed. This tension led to the very excellent result that

the findings were hammered out with great care and thoroughness, and an

exceedingly careful distinction was made between the conclusions that

could

be proven by the evidence, and the conclusions that were founded

primarily

on metaphysical assumptions. This great care and thoroughness is one of

the reasons why the rapid change in viewpoint after Darwin’s

Origin

of Species appeared was so unsettling to Lydia Miller.

Are the points of contention the valid findings of objective

science?

And are the points central to the argument — are they truly telling

blows,

or just arguable points on the periphery?

I will list some of the arguments of the new geology that seem to me

to be most significant, so you can get an idea of the scope of the

matter.

Of course, most of these points are discussed at length in the

geological

books of the time, to which you may wish to go for further information.

… By the Theologians. At one extreme sat the theologians.

There

were three primary areas of contention.

1. Age of the Earth. One early conclusion of the geologists

was

that the earth is very old. They did not have the tools to put a

precise

number on the age of the earth, but it was clear to them that the age

is

at least in the many millions of years.

2. Universal Flood. At first blush, the evidence that most

of

the earth was once covered with water was seen as proof of Noah’s

flood.

But it was pointed out by scientists as early as Robert Hooke

(1635-1703),

more than a century earlier, that Noah’s flood was both too violent to

account for the vast layers laid down under tranquil conditions and too

calm to account for the great dislocations that resulted in marine

fossils

existing on high mountains.19

3. Death prior to Adam. “[Geology] distinctly testifies to

the

occurrence of death among animals long before the existence of man.”20

So, geology was seen to contradict what were believed by many

theologians

to be assertions of the Holy Scriptures: that the earth was created

very

shortly before man; that death came about as a result of Adam’s sin,

and

that there was a global flood. These views are based on the most direct

and literal interpretation of the Bible, and are still quite popular

today

among many evangelical Christians. It is not surprising that those who

accept this interpretation of Genesis would have severe problems with

any

science that claimed findings that contradict these views.

As an aside it is interesting to note that a number of evangelical

scholars

of the late 19th and into the early 20th century, accepted these

findings

of geology; for example, the widely used 1917 edition of the Scofield

Bible

did21, as

did

a number of conservative Bible scholars of the time, such as Charles

Hodge.22

… By the Naturalists. At the other extreme from the

theologians,

opposition came from what were called “naturalists”, those who believe

that the world of living species came about by purely natural

processes,

and deny the need for a transcendent Creator. With apologies to the

theologians

among you, I would like to pay particular emphasis to this side of the

controversy, because it goes to the heart of the current arguments

about

evolution.

For the naturalist, life developed from non-life by natural means.

Advanced

life developed from primitive life. All of the marvelous features of

all

living creatures, came about by mindless natural processes, without any

need for a Creator.

This naturalistic viewpoint came as a philosophical

pre-disposition,

which dates back to the ancient Greeks. In the contemporary context of

19th century geology, the prominent people who argued for naturalism

included

Voltaire (1694-1778) and Lamarck.23

Clearly, a naturalist must believe that the present system of living

species came about by some form of spontaneous generation, and by

evolution,

called “progressive development” by Lyell and other early geologists.

Spontaneous

generation was coming under a severe cloud at the time,24

although Pasteur’s definitive experiment did not take place until 1859,

the same year as Darwin’s Origin of Species appeared.

Lamarck (1744-1829) was a prominent proponent of progressive

development,

in opposition to Linnæus (1707-1778). The issue was posed in the

form of a question: “Is there such a thing as ‘species?’” In other

words,

are there essential limits to their progressive development (as

Linnæus

affirmed) that separate various kinds of plants and animals, or is it

possible

for any kind to be linked to any other kind by purely natural

variation?

Lamarck argued that species is a useful concept only in the short

run:

given enough time anything can be related to anything else.

Linnæus

argued that there are essential limits that define species and cannot

be

crossed by natural processes.

Lyell, the geologist, stated that the position of Lamarck finds no

confirmation

in the fossil record: the appearance of new fossil kinds is sudden, and

there is no evidence, even in the long geological ages, for a species

to

develop a major innovation. He remarked that the arguments that Lamarck

cites only go to show that certain attributes of a species can be

enhanced

or diminished over time, but “no positive fact is cited to exemplify

the

substitution of some entirely new sense, faculty, or organ, in the room

of some other suppressed as useless....”25

He goes on:

“ It is evident that, if some well-authenticated facts could have

been

adduced to establish one complete step in the process of

transformation,

such as the appearance, in individuals descending from a common stock,

of a sense or organ entirely new, and a complete disappearance of some

other enjoyed by their progenitors, time alone might then be supposed

sufficient

to bring about any amount of metamorphosis. The gratuitous assumption,

therefore, of a point so vital to the theory of transmutation, was

unpardonable

on the part of its advocate.”26

But I am getting a bit ahead of myself. What were the findings of

19th

century geology that appeared to contradict the positions of the

naturalists?

Here are some of the points cited in a number of geology books by the

1850s.

• There was a beginning. Among intellectuals of the time,

belief

that matter and life were part of a non-ending cycle of existence was

connected

with atheism, notably the pantheism of Spinoza. This belief was thought

to be a matter of philosophy; it was a great surprise that geology

could

defeat the belief, as far as it concerned life.

Geology revealed that the earth began as a molten mass. One proof of

this (among several) is the oblate spheroid shape of the earth (the

poles

are flattened) which is characteristic of a rotating molten mass.27

Obviously, then, the early earth was not habitable by any sort of life,

and so life began a long, but not infinite, time ago. “all things

remain

as they were from the beginning until now,” is not possible. It is

provably

wrong.

Obviously life cannot exist on a molten Earth, so life clearly had a

beginning. Furthermore, as the fossil evidence accumulated it became

clear

that the various kinds of life – phyla, classes, families – also had

beginnings,

and that these beginnings were spaced out in an orderly sequence

through

the fossil record.

I should note that the early geologists observed that rocks beneath

the Cambrian strata had no fossils, and so they set the beginning of

life

to the commencement of the Cambrian age. We now know that many of these

rocks underlying the Cambrian age are populated with microscopic

fossils,

which may even leave quite visible evidence, such as the stromatolytes.

The fossils known to the early geologists come from what is now known

as

the Phanerozoic era, that is, the age of visible fossils, which

began with the Cambrian age. The name distinguishes this era from the

earlier

era, now called the Cryptozoic era, when the fossils were microscopic.

We know today that microscopic life existed virtually back to the

very

first time that the earth had cooled sufficiently for oceans to

condense

from the atmosphere, and that these early creatures built up -- over

literally

billions of years -- the oxygen atmosphere and available nitrogen that

are essential for the visible animals to exist.

This one fact, that life had a finite beginning, poses the problem

of

spontaneous generation. Either life was created by a God or gods, or it

arose naturally by spontaneous generation. For a naturalist,

spontaneous

generation is an essential belief, despite the growing evidence against

it.

• The Earth as a whole is hostile to life. We live on a thin

shell over a hot, inhospitable interior and under a cold, inhospitable

cosmos. The actual volume that is habitable is minute.

Furthermore, the two great engines for change on earth – fire and

water

– are essential to the development of life, but are potentially ruinous

for life to continue. Quoting Hitchcock,

“In the mighty intensity of their action in early times, we can

hardly

see how there could have been much of security or permanence in the

state

of the globe ... We feel as if the earth's crust must have been

constantly

liable to be torn in pieces by volcanic fires, or drenched by sweeping

deluges. And yet the various economies of life on the globe, that have

preceded the present, have all been seasons of profound repose and

uniformity.

… it must have required infinite wisdom and power so to arrange the

agencies

of nature that the desolating action of fire and water should take

place

only at those epochs when every thing was in readiness for the ruin of

an old economy and the introduction of a new one.”28

The conditions required for life to exist are exceedingly narrow: at

the very least the conditions are bounded between the freezing and

boiling

points of water. But in addition there must be available nutrients in

sufficient

quantity, and as the species complexity increases, the specific

requirements

for life become more and more particular, and the species’ grip on life

is increasingly tenuous.

And yet the earth has been host for life continuously since the

first

life appeared. To Hitchcock, this implies that the development of life

did not proceed randomly but was under the control of a divine power.

I should note that to anyone who does not accept the truth that God

providentially sustains the world, the fragility of the ecosystem, and

its existence amid hostile surroundings can be a cause of great

anxiety,

and leads to extraordinary efforts to attempt to control the ecosystem

by human effort.

• There is an arrow of development and progression over

geological

history. The earth’s history shows a gradually increasing

capability

to sustain progressively more complex forms of life. At many stages in

this process, the ecosystem at that stage relied on the products of

earlier

stages, and the living species that appear for the first time, could

not

have survived at an earlier stage. In particular, modern life could not

exist without the preparation of those earlier stages.

The appearance, then is that of deliberate design with the specific

end of human habitation in view. Hitchcock argues,

“Every successive change of importance on the earth's surface

appears

to have been an improvement of its condition, adapting it to beings of

a higher organization, and to man at last, the most perfect of all.”29

The progression through these stages is all the more remarkable in

view

of the very restricted conditions in which life of any sort can be

sustained.

Even the “primitive” species in those earlier worlds, had to be

exquisitely

adapted to survive, beginning with the very first living species.

• All of Life shows a unity of design from the very first

appearance

in the fossil record. The collection of body plans (phyla) that

characterize

modern species is unchanged throughout all of the Earth’s history. All

fossil species are recognizably similar in design to modern species.

Buckland wrote,

“It has not been found necessary, in discussing the history of

fossil

plants and animals, to constitute a single new class; they all fall

naturally

into the same great sections as the existing forms.” 30

Here, Buckland uses the term “class” in the technical sense used in

biological classification, which divides the animal and plant kingdoms

into the groupings: phyla, class, order, family, genus and species. For

example, mammals and birds form two of the classes of the vertebrates.

Thus Buckland makes the remarkable assertion: there are no unfamiliar

classes

in the fossil record.

Among other things, this unity argues against multiple creators

(gods)

and spontaneous generation. Paley, writing in 1802, notes:

“We never get amongst such original or totally different modes of

Existence,

as to indicate that we are come into the province of a different

Creator,

or under the direction of a different WiIl. In truth the same order of

things attends us wherever we go.”31

• The fossil record is characterized by annihilation followed by

innovation. Many of the strata have very distinct boundaries, at

which

the nature of the fossils change dramatically with the sudden

disappearance

of some species followed by the sudden appearance of new kinds. In some

cases the cause is clearly related to the rising or sinking of the

land,

but in other cases the change is even more dramatic, as in the Permian

extinction before birds and large mammals appeared, and at the end of

the

dinosaur age, called the K-T boundary.

• The record is characterized by sudden innovations, not gradual

change.

-- All of the basic body plans appear suddenly in the

earliest

fossils during the Cambrian age. This fact was noted by Buckland in

reference

to the earliest fossil-bearing rocks.

-- Major innovations arise suddenly. What is true for the

very

earliest fossils also holds for major innovations in the plant and

animal

kingdom: they arise suddenly in the fossil record with no evident

transitional

fossils. This results in the well-known “gaps”. Buckland notes:

“It appears that the character of fossil Fishes does not change

insensibly

from one formation to another, as in the case of many Zoophytes and

Testacea;

nor do the same genera; or even the same families, pervade successive

series

of great formations; but their changes take place abruptly, at certain

definite points in the vertical succession of the strata, like the

sudden

changes that occur in fossil Reptiles and Mammalia.”32

The gaps were well-recognized by Darwin, but the general thought

among

the naturalists was that the gaps were the result of the incomplete

nature

of the fossil discoveries. However the gaps persist to this day, and

the

number of examples of supposed transitional specimens is infinitesimal

in comparison with the number of gaps.

• There is no fossil evidence of species “improving” except as

appears

to be provided for within the limits of the species.

Buckland also noted that the first examples of a major innovation in

the fossil record are often quite advanced, and the effect of time

often

appears to lead to a reduction of ability rather than the reverse as

evolution

would seem to require. An example is the ammonites, to be mentioned

shortly,

and the loss of features, such as sight in cave fish.

- Anticipation. Lyell goes even further in that he

argues

that a species, when it first appears, seems already to have the

ability

to adapt to the circumstances that it will face.

"We must suppose that when the Author of Nature creates an animal or

plant, all the possible circumstances in which its descendants are

destined

to live are foreseen, and that an organization is conferred upon it

which

will enable the species to perpetuate itself and survive under all the

varying circumstances to which it must be inevitably exposed."33

• The fossil body plans show fitness and harmony in all details.

There

are no “hopeful monsters” in the fossil record. If the record were able

to be characterized in that way, then it would not have been possible

for

Cuvier, an early Geologist, to infer the function, habitat and general

features of a species from a single limb, bone or even a single tooth.

Buckland stated,

“We can hardly imagine any stronger proof of the Unity of Design and

Harmony of Organizations that have ever pervaded all animated nature,

than

we find in the fact established by Cuvier, that from the character of a

single limb, and even of a single tooth or bone, the form and

proportions

of the other bones, and condition of the entire Animal may be inferred.”34

This argues against unguided innovation of body parts.

• The fossils show exquisite innovations that address intricate

design

challenges. The early geologists spend a lot of time examining the

details of how the fossil species carried on their lives, discovering

evidence

of exquisite fitness for the particular environment that those fossils

enjoyed. Lyell, Buckland, Hitchcock and others give detailed examples

of

the amazing engineering contrivances of ancient fossil species, many of

which vanished — together with their exquisite adaptations — over the

course

of time, but preserved in the fossil record.

Buckland, in particular, devoted a large part of his writing to the

ammonites (now extinct), shell fish that use flotation chambers to

control

their feeding depth. In some instances, the fossil species used

engineering

contrivances that are more complex than modern species. He states,

“We are almost lost in astonishment, at the microscopic attention

that

has been paid to the welfare of creatures, holding so low a place…. If

there be one thing more surprising than another in the investigation of

natural phenomena, it is perhaps the infinite extent and vast

importance

of things apparently little and insignificant.”35

“From the high preservation in which we find the remains of animals

and vegetables of each geological formation [both hard and soft body

parts

– dcb], and the exquisite mechanism which appears in many fossil

fragments

of their organization, we may collect an infinity of arguments, to show

that the creatures from which all these are derived were constructed

with

a view to the varying conditions of the surface of the Earth, and to

its

gradually increasing capabilities of sustaining more complex forms of

organic

life.”36

These, in summary, are some of the findings that the geologists came

to by the mid-1800’s. Many of the geologists, including Lydia Miller,

viewed

these findings as powerful testimony to a divine creator.

Modern Confirmation of these Findings.

Continued advancement in geology to the present day strengthens a

number

of these conclusions of the 19th century geologists. For example:

• Regarding the Beginning. It is now known that not only

life,

but matter and the universe itself had beginnings. A thorough

understanding

of nuclear physics and the nature of radioactivity allows precise

dating

of the age of the universe, of the sun, of earth, and of all of the

strata

in the geological record.

•Regarding the Beginning of Life. It is now known that the

simplest

possible self-sustaining cell requires a genetic code of over 1,750,000

base pairs, and over 2000 genes.37

How is this to arise spontaneously?

It is now understood that the earliest time that life could have

existed

on earth is about 3.9 billion years ago, when the earth’s crust first

hardened

and cooled enough for water to condense into the oceans. There is

indirect

evidence of life as early as 3.8 billion years ago38,

and actual fossils have been found dating to 3.65 billion years ago.

These

fossils already had the exceedingly complex chlorophyll light-to-energy

conversion and nitrogen fixing processes.

This early appearance of life, severely limits the time available

for

it to arise spontaneously. There is no known process that would lead to

such complexity of end result by purely random means using the known

natural

laws of physics and chemistry.

• Regarding the complexity of the simplest cell, it is known

that even the simplest cell relies on exceedingly complex processes

that

occur on the sub-microscopic level, such as the transport systems

involving

kinesin motor molecules that travel over the cytoskeleton microtubules.

It is known that the basic body plans are implemented by an elaborate

and

delicate control process involving special “hox” genes. How are these

to

be had by random, undirected processes?

•Regarding the unity of species. It is now know that all

living

species use the same genetic coding scheme (with only very minor

changes

that can be plausibly accounted for by random variation), and follow

the

same complex “central dogma” for converting the DNA code into molecules

of life.

It is difficult to even imagine how the complex central dogma —

which

itself requires over 150 separate genes involving over 150,000 DNA base

pairs — could have arisen by naturalistic means. Furthermore, if life

appeared

by spontaneous generation, why is there only a single example of the

“central

dogma?” Why not multiple dogmas, corresponding to multiple instances of

spontaneous generation?

• Regarding Sudden Innovations. The near-simultaneous

appearance

of all animal body plans is now accepted as a fact and that all of the

30-odd phyla of animals have their first appearance in the Cambrian

rocks.

Some geologists even assert that they all appeared within a

(geologically)

very short interval of time, perhaps as little as 5 million years. The

body plans arrive in the record without any clear relationship to

complexity.

For example, trilobites, one of the earliest fossils to appear in the

record,

come complete with all of the major bodily systems – eyes, antennas and

olfactory pits for sensors, a full digestive system, circulatory system

with a heart, nervous system with ganglia, muscular system, and an

articulated

exoskeleton.

• regarding the gaps in the fossil record. The sudden

appearance

of major innovations is well-attested in the fossil record, and can no

longer be attributed to an incomplete record. Indeed, the fact has been

given a name: punctuated equilibrium. The gaps have sharpened, not

diminished,

and the number of proposed “transitional” fossils is miniscule in

comparison

with the number of acknowledged gaps.

In summary, the modern evidence only confirms and extends the main

findings

of the 19th century geologists, and the evidence in favor of naturalism

is not strengthened in even a single point.

Conclusion.

So what do we make of all of this? Is there powerful evidence in

favor

of a Creator, as many geologists believed prior to the appearance of

Darwin’s

book?

Well, these arguments seem powerful to me, and these are only a

fraction

of the evidence that is offered in the geologists’ writings of the

time.

I have intentionally omitted some of what I might call “fit” design

arguments,

along the lines used in Paley’s book; such arguments are quite

convincing

to a person who is already inclined to believe in the reality of a

Creator,

as I am myself, but don’t carry much weight with a dogged agnostic.

For example, Buckland and Lyell note that the very ruggedness of the

terrain — the high mountains and the exposed upliftings — are examples

of God’s providence because they are necessary for man’s well-being.

Lyell’s

Principles

has an extensive discussion of climate and notes that mountains help to

control weather patterns, particularly rainfall. Alternations of

permeable

and impermeable rock strata facilitate the watering of the lowlands by

in effect providing natural aqueducts that channel water from the

mountains

to the lowlands. In particular, London and Paris benefit from this

effect.

Buckland argued that the coal built up during the carboniferous age

(the only geologic age with substantial coal formation), fueled the

modern

industrial age, and without it, civilization would still be an agrarian

society with severe fuel scarcity limiting progress. And without the

uplifting

of the land and exposure of the carboniferous rocks, the coal would

have

been inaccessible, and its qualities probably not even known.

But even leaving these arguments aside, the evidence that we have

noted

in favor of a Creator is very powerful. How can science ignor them? Why

did this evidence disappear from the geological literature?

I believe that Lydia Miller has it right: science just doesn’t

contemplate

it, but removes it “to a more distant and dimmer region.” Admitting the

possibility of a Creator is viewed as outside of the purview of

science.

By implication, those 19th century Geologists were acting improperly to

point out the evidence in favor of a Creator.

I believe that there is also another factor that contributed to the

disappearance. After 1859 the double opposition from theologians and

naturalists

that had forced the early geologists to use great care and thoroughness

in their claims, largely vanished from the scene. The Darwinian thesis

fell completely within the naturalist camp, which eliminated opposition

from that side, and the new generation of scientists no longer felt an

obligation to give serious attention to the theological views, as

removed

from the purview of science. A dark climate of intellectualism was

rising,

which over the next century, would lead to terrible worldwide

devastation

and destructive global warfare: social darwinism, the concept of

superior

races, communism and other terrible and perverse consequences of

intellectualism

gone awry.

But the evidence, objectively considered, DOES point to a Divine

Creator;

this evidence is not philosophical, it is concrete and can be tested.

Attempts

have been made to disprove its findings for over 150 years, without

success;

only by removing the evidence to the dimmer regions, can it be ignored.

It is the “silent voice” of geology, declaring God’s glory.

David C. Bossard

Lebanon, New Hampshire

March, 2003

Bibliography

| 1758 |

Carl von Linné (Linnæus), Systema

Naturae:

Creationis telluris est gloria dei ex opere Naturae per Hominem Solum.

10th. Ed. |

| 1749- |

Georges Buffon, Historie Naturelle, in 44

volumns between

1749 and 1804. |

| 1802 |

William Paley, Natural Theology |

| 1809 |

Lamarck, Jean Baptiste de Monet, Chevalier de

Philosophie

Zoologique |

| 1825 |

Baron Georges Cuvier, A Discourse on the

Revolutions of

the Surface of the Globe, English Translation 1831. |

| 1832- |

Sir Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 8th

Ed. 1850 and

Manual of Elementary Geology , 6th Ed. 1855. |

| 1837 |

William Buckland, Geology and Mineralogy,

Considered with

Reference to Natural Theology, Volume VI of the Bridgewater

Treatises. |

| 1840 |

John Pye Smith, On the Relation between the Holy

Scriptures

and some parts of the Geological Sciences. |

| 1841 |

Edward Hitchcock, Elementary Geology 31st

Edition, 1862. |

| 1847- |

James Hall, Natural History of New York 8 Vols.

between

1847-1894. |

| 1851 |

Hugh Miller, Footprints of the Creator 3rd Ed.

1858. Compiled

by Lydia Miller. |

| 1851 |

Edward Hitchcock, Religion of Geology. |

| 1857- |

Louis Agassiz, Natural History of the United

States of America,

4 vols. |

| 1857 |

Hugh Miller (1802-1856), Testimony of the Rocks.

Compiled

by Lydia Miller. |

| 1859 |

–– Sketchbook of Popular Geology, 4th Ed. 1869.

Compiled

by Lydia Miller. |

| 1859 |

[Pasteur’s Experiment proving spontaneous

generation does

not occur.] |

| 1859 |

Charles Darwin, Origin of Species |

| 1862 |

Lord Kelvin, On the Secular Cooling of the

Earth. |

| 1863 |

James Dana, Manual of Geology, 4th Ed.

1896. |

| 1870 |

Alexander Winchell, Sketches of Creation |

| 1878 |

Sir Andrew Crombie Ramsay, Geology of Great

Britain 5th

Ed. 1878. |

| 1901 |

Karl Alfred von Zittel, History of Geology and

Palæontology

to the end of the Nineteenth century. |

| 1987 |

Daniel Wonderly, Neglect of Geologic data:

Sedimentary Strata

Compared with Young-Earth Creationist Writings. |

| 1999 |

Size Limits of Very Small Microorganisms,

National Research

Council, 2000. Text is available at

http://www.nationalacademies.org/ssb/nanomenu.htm. |

| 2002 |

Simon Winchester, The Map that Changed the

World: William

Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology. Perennial. |

APPENDIX

The Problem of the Source of the Earth's Heat

Energy

One of the dilemmas that the early geologists faced was that the

understanding

of physics and chemistry in the mid 1800s could not account for the

evident

presence of heat energy in the Sun and in the earth’s interior. More

particularly,

the geologists could not reconcile the evident old age of the sun and

earth

with the continued expenditure of vast amounts of heat energy over that

time.

In 1862, Lord Kelvin estimated the age of earth at 98 million years

based on cooling from a molten state.39

This assumed that the heat generation followed the known laws of

physics

and chemistry. As to the Sun, one theory was that the Sun’s fuel was

constantly

renewed by meteorites from space; otherwise the Sun would also burn out

over a time measured in millions of years.

It is greatly to their credit that geologists persisted in the view

that the primary source of energy for the earth’s changes came from

heat

generated in the earth’s interior, despite the apparent contradiction

between

this view and their understanding of physics and chemistry. By the late

1800s, the geologist James Dana gives the age of the earth as “probably

24,000,000 years” with extreme estimates from 10 million to 6 billion

years40,

which range does in fact span the current estimate of 4.55 billion

years.

The bias in favor of the lower values was undoubtedly influenced by

Lord

Kelvin’s estimate.

The answer, which was not understood until well into the 20th

century,

is that nuclear energy is the source of the heat both in the Sun and in

the earth’s interior. For the Sun, the energy results from nuclear

fusion,

primarily of hydrogen into helium, and for the Earth the energy comes

from

nuclear fission, the radioactive decay of uranium and other heavy

elements.

This is the reason why the Earth’s interior has not cooled and has

always

been partially molten.

I might mention one interesting incident about this misunderstanding

of the importance of nuclear energy. William Buckland (1784-1856) was a

contemporary of Lyell who wrote a treatise in 1837 on geology.41

This book is a strong defence of the consistency of the Bible with the

findings of geology.

At one place in this book42

, he mentions 2 Peter 3:10, "But the day of the Lord will come like a

thief,

in which the heavens will pass away with a roar and the elements will

be

destroyed with intense heat, and the earth and its works will be burned

up." He argues that the "destruction" is not of the earth but of matter

on the earth. He explains, "The common opinion is, that intense

combustion

actually destroys or annihilates matter... But the chemist knows that

not

one particle of matter has ever been thus deprived of existence; that

fire

only changes the form of matter, but never annihilates it." So he then

goes on to explain that burning is oxidation, and that what will be

annihilated

is the burnable matter on earth "since biblical and scientific truth

must

agree, we may be sure that the apostle never meant to teach that the

matter

of the globe would cease to be, through the action of fire upon it." He

goes on, "the passage under consideration teaches us that whatever upon

or within the earth is capable of combustion will undergo that change,

and that the entire globe will be melted."

Of course, with our more accurate understanding of the nature of the

elements, we know that the elements can indeed be destroyed, and that

oxidation

is not the only means of change in a substance. In fact, with an

understanding

of nuclear processes, the passage in Peter takes on new and awesome

significance.

FOOTNOTES

1 Hugh

Miller (1802-1856), Sketchbook of Popular Geology, 4th Ed.

1869,

Preface p. xxx. The Sketchbook was edited and published posthumously by

his wife, Lydia Miller. The first edition was published in 1859. See

http://www.hughmiller.org/

for more on Hugh Miller. Other books, also written by Hugh Miller and

brought

into publication by his wife, include: Testimony of the Rocks

(1857),

and Footprints of the Creator (1851).

2 For example:

Georges

Cuvier (1769-1832), William Conybeare (1787-1857), William Buckland

(1784-1856),

Hugh Miller (1802-1856), Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892), Sir Andrew

Ramsay

(1814-1891), Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), James Dana (1813-1895), Edward

Hitchcock (1793-1864), and Alexander Winchell (1824-1891). Books that

specifically

concern natural theology include Hugh Miller’s books cited above, and

William

Buckland, Geology and Mineralogy, Considered with Reference to

Natural

Theology, 1837; Edward Hitchcock, Religion of Geology and its

Connected

Sciences, 1851. Buckland’s work (2 volumes) was Treatise VI of The

Bridgewater Treatises on the Power Wisdom and Goodness of God as

Manifested

in the Creation, published in the 1830’s.

3 William Paley,

Natural

Theology, 1802.

4 William

Buckland,

Geology

and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology,

Volume

VI of the Bridgewater Treatises, 1837, p. 672ff.

5 Carl von

Linné

(Linnæus), Systema Naturae: Creationis telluris est gloria

Dei

ex opere Naturae per Hominen Solum. 10th Ed. 1758.

6 See Simon

Winchester,

The Map that Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of

Modern

Geology. Perennial, 2002.

7 Adapted from a

map

in A. C. Ramsay, The Physical Geology and Geography of Great Britain,

1878.

8 Winchester, p.

128

ff. An original copy (one of three) of the table is preserved at the

Geological

Society of London.

9 Lyell,

Principles,

p. 60 “Smith adopted for the most part English provincial terms, often

of barbarous sound, such as gault, cornbrash, clunch clay; and affixed

them to subdivisions of the British series. many of these still retain

their place in our scientific classifications, and attest to his

priority

of arrangement.”

10 A

version of this table, published in 1801 can be viewed at the

University

of New Hampshire web site dedicated to William Smith, at http://www.unh.edu/esci/wmsmith.html.

11 William

Smith's map can be viewed at the University of New Hampshire web site,

op.

cit.

12 Georges

Cuvier,

Revolutions of the Earth, [1825 (French; English Translation

1831)]

p. 36.

13 Edward

Hitchcock, Religion of Geology, 1851. p. 57: “stratified rocks

are

… six and a half miles thick in Europe, and still thicker in this

country

(i.e. in the United States – dcb)… the manner in which the

materials

are arranged, and especially the preservation of the most delicate

parts

of the organic remains, often in the very position in which the animals

died, show the quiet and slow manner in which the process went on.”

14 Wonderly,

Neglect

of Geologic Data, 1987, gives examples.

15 Hitchcock,

p. 35-39.

16 A

curious historical fact is that this uniformitarian view came to be

such

an ingrained dogma that geologists were very slow to accept two of the

most important current views: Tectonic plate theory; and the

explanation

for mass exterminations at the so-called K-T boundary, the result of a

meteorite hitting the earth (a large meteorite hit the earth in the

vicinity

of the Yucatan Penninsula about 65 million years ago). I think the

objection

was that these theories appeared to be a threat to a uniformitarian

viewpoint.

Maps of active volcano sites that are included in Lyell’s books clearly

trace the outlines of the major tectonic plates, and evidence provided

by Lyell and his contemporaries for the movements of large land masses

might have suggested the existence of tectonic plates even as early as

the mid-19th century; yet the conclusion was delayed for over a century.

17 Hitchcock,

p. 31-35

18 See Appendix

A

for a discussion of the problem of heat energy.

19 Hooke, cited

in

Lyell, Principles, p. 31 and Edward Hitchcock, Religion of

Geology,

1851.

20 Hitchcock,

ibid.

p. 35.

21 C.I.

Scofield,

The Scofield Reference Bible, 1917. Note 2 on Genesis 1:1

(creation

of the heavens and the earth) states, “The first creative act refers to

the dateless past, and gives scope for all the geologic ages.”

Similarly,

Scofield states that the word “day” may be understood to mean other

than

24 hours (Note 1,2 on Genesis 1:5) and adds, “Each creative ‘day’ was a

period of time marked off by a beginning and ending.”

22 Charles

Hodge,

Systematic Theology, (1st Ed. 1871) Vol. 1 p. 570 favorably

cites

James Dana’s Manual of Geology as an authority.

23 Lamarck’s

Philosophie

Zoologique published in 1809 was an early proponent of progressive

development, or evolution as it is known today.

24 Hitchcock

wrote in 1851, “As instruments have been improved, and observations

have

become more searching, the supposed cases of spontaneous generation

have

diminished, until it is not pretended now that it takes place except in

a very few tribes, and those the most obscure and difficult to observe

of all living things.” Religion of Geology, p. 262. By

implication,

as instruments improve and can penetrate those “most obscure” crevices,

spontaneous generation will be seen to be a chimera.

25 Lyell,

Principles,

p. 549.

26 Lyell,

Ibid.

27 Edward

Hitchcock,

The

Religion of Geology, 1851, p. 142. There were two lines of proof

available

to 19th century geologists: direct measurement of the distance along a

longitudinal line between two latitudes (the distance increases toward

the poles); and measurement of changes in the rate of a pendulum ,

measured

at different latitudes (Paris and the Cayenne Islands in the first

instance

-- a difference of 2 minutes, 28 seconds per day), related to small

changes

in the gravity caused by different radial distances to the center of

the

earth. For an early discussion, see W. Mullinger Higgins,

The Earth:

Its Physical Condition and most Remarkable Phenomena, Harper, 1858,

p. 25ff andp. 33. The pendulum observations were published by M.

Richter

about 1650. Among others, Mason and Dixon made such measurements in

1763,

in connection with the surveys of the Mason-Dixon line that defines the

southern border of Pennsylvania. For a treatise on the Figure of the

Earth,

see http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/somerville/11.htm.

28 Ibid,

p.

275.

29 Hitchcock,

pp. 35-39.

30Buckland, Ibid.

p. 61.

31 William

Paley, Natural Theology, 1802 – reprint Harper 1840, 2 vols.

Vol.

2, Ch. XXV p. 143.

32 Ibid.

p.

272.

33 Lyell,

Principles,

p. 560.

34 Buckland,

ibid.

p. 109.

35 Ibid.

p.

442, 445.

36 Ibid.

p.

107.

37 See David C.

Bossard,

The Chemical Buildingblocks of Life, IBRI Research report #50,

available

at http://www.ibri.org.

38 For

example, the relative abundance of isotopes of carbon differs if the

carbon

is inorganically produced or has passed through the chemistry of life.

This isotopic analysis of early rocks indicates the very early presence

of life, even though fossils are not present.

39 Lord Kelvin,

On

the Secular Cooling of the Earth, 1862.

40 James Dwight

Dana

(1813-1895), Manual of Geology, Fourth Edition 1896, p. 1026.

41 Rev. William

Buckland,

D.D. Geology and Mineralogy, considered with reference to Natural

Theology,

2nd. Ed. 1837. This argument is repeated in Edward Hitchcock, Religion

of Geology, 1851, p. 22, “It is probably the prevailing opinion

among

intelligent Christians at this time, and has been the opinion of many

commentators,

that when Peter describes the future destruction of the world, he means

that its solid substance, and indeed that of the whole material

universe,

will be utterly consumed or annihilated by fire. This opinion rests

upon

the common belief that such is the effect of combustion. But chemistry

informs us, that no case of combustion, how fiercely soever the fire

may

rage, annihilates the least particle of matter and that fire only

changes

the form of substances…Has Peter, then, made a mistake because he did

not

understand modern chemistry? … [No,] He no where asserts, or implies,

that

one particle of matter will be annihilated by that catastrophe.”

42 Ibid.

p. 304ff.

You

can contact IBRI by e-mail at: webmaster@ibri.org

You

can contact IBRI by e-mail at: webmaster@ibri.org

Return to the IBRI Home Page

Last updated: July 18,

2003;

Hyperlinks updated 18-Jul-2003

You

can contact IBRI by e-mail at: webmaster@ibri.org

You

can contact IBRI by e-mail at: webmaster@ibri.org