2.3 Evidence from Physical Anthropology (continued)

2.3.4 Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. H. erectus and

H.

neanderthalensis are the two better documented early human fossils

that trace the history of human beings back to the glacial periods. In

addition to the large cranial capacities of these two species, the cultural

remains also lend much support to their being human fossils. H. erectus

was

found not only with tools made of chipped stone and bone but also charred

deer bone, a fact that strongly suggests they had learned to cook with

fire. H. neanderthalensis had better-quality stone tools and buried

their dead. Figures 2.20, 2.21 and 2.22 compare H. erectus with

H. neanderthalensis, H. erectus with modern humans, and H. neanderthalensis

with

modern humans, respectively.

a) Homo erectus Discussed. The original find of H. erectus

was

made in Java in 1890-91 and includes fragments of a skull and a femur.

It was designated as Pithecanthropus erectus. Subsequently, various

skulls and jaws were found in Java, China, Hungary, Germany, Algeria, Morocco,

South Africa, and Tanzania (Table 2.12). The best documented among them

was the Sinanthropus pekinensis with many fragments of 15 skulls

and 11 mandibles found near Peking, China. It was renamed H. erectus

pekinensis and dated by an amino acid racemization technique (23)

to be around 300,000 to 500,000 years old. Analyzed fossil fauna associated

with the human fossils are suggestive of the climatic change of [109]

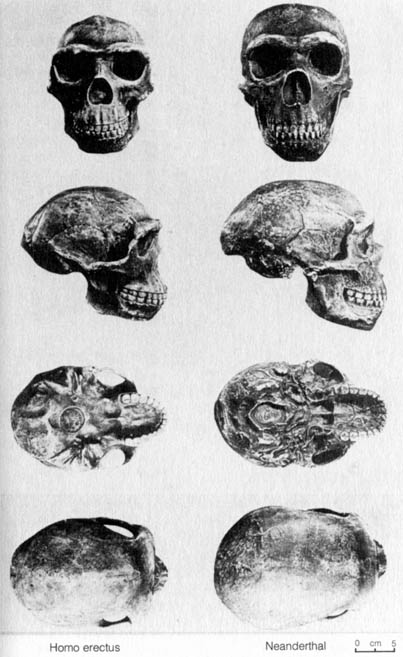

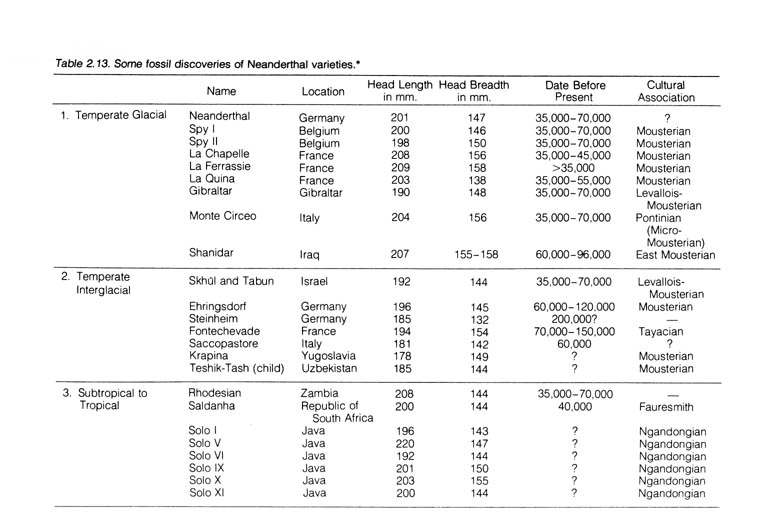

Figure 2.20. Comparison of four views of Homo erectus

with a Neanderthal skull cast. Reprinted, with permission, from Kelso,

A. J. Physical anthropology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott &

Co.; 1970. [110]

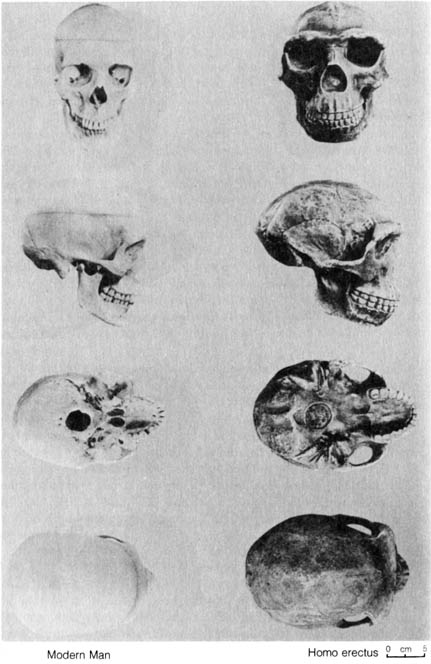

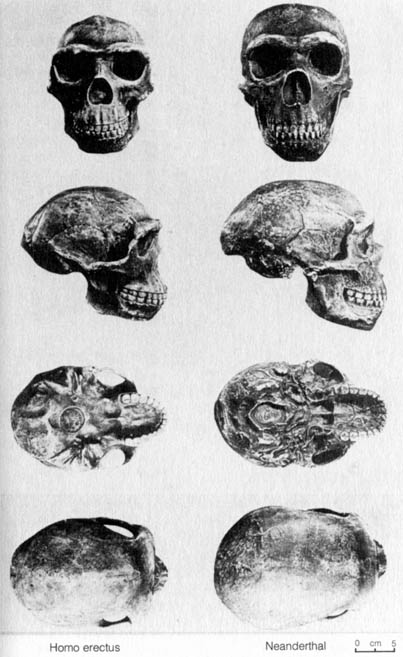

Figure 2.21. Comparison of four views of a modern human

skull with a Homo erectus. Reprinted, with permission, from Kelso,

A. J. Physical anthropology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott &

Co.; 1970. [111]

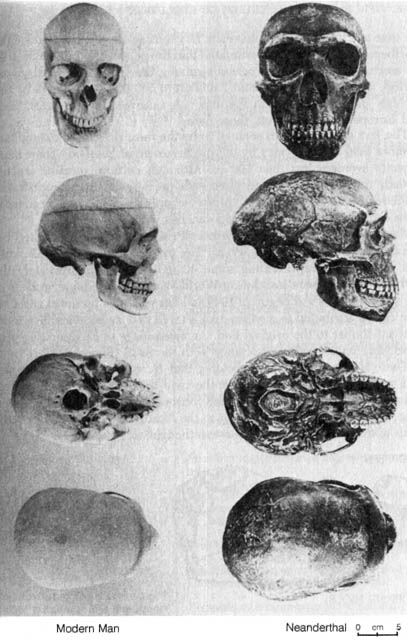

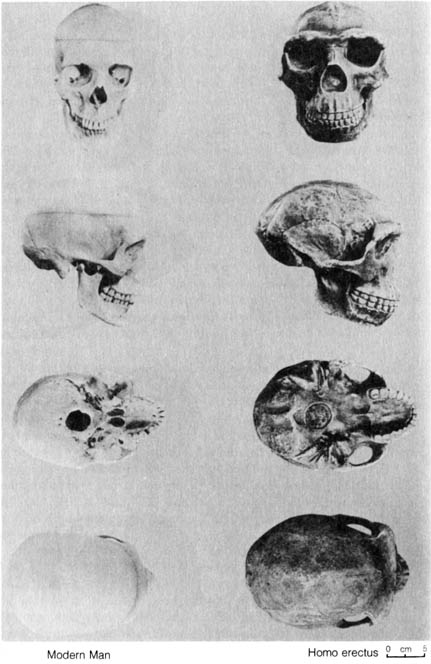

Figure 2.22. Comparison of four views of a modern human

skull with a Neanderthal skull cast. Reprinted, with permission, from Kelso,

A. J. Physical anthropology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott &

Co.; 1970.

[112] the time and have helped to correlate H. erectus with the

glaciation of the Northern Hemisphere. It is estimated that the period

of time occupied by H. erectus appears to be a period spanning the

first and second glacial period, and this is roughly from 1 million to

500,000 years ago (24). The absolute dating estimates

on the materials uncovered from Africa, Java, and Europe also corroborate

these dates.

The Java group of fossils seemed to be the most primitive, dating back

to more than 710,000 years by the potassium-argon method. Their brain capacity

averages less than 900 cc. Although cultural remains are not directly found

in the original place with the Java fossils, circumstantial evidence indicates

the oldest chopper-chopping stone tools recovered from central Java may

be contemporaneous with the fossils.

The H. erectus found in a cave near Peking was the best studied

because of the abundance of materials. The original find included 15 skulls

and other bones representing some 40 individuals. Unfortunately the early

discoveries were lost during World War II. Subsequent work from the same

deposits was begun in 1949 and has yielded a humerus and tibia that can

be attributed to modern man, as well as a jawbone and five teeth that are

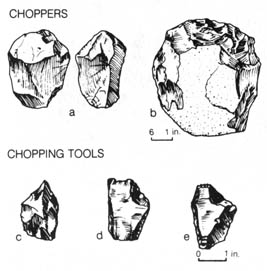

similar to the original find. An assemblage of chopper-chopping tools were

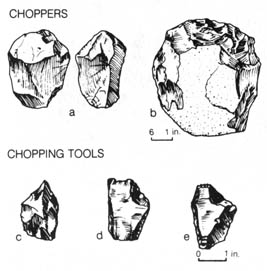

uncovered in association with the fossil (Figure 2.23).

There is strong evidence indicating that H. erectus knew how

to use and control fire. The evidence at the cave deposits includes fireplaces

found at several locations and many burned or charred fossil bones of other

animals presumably brought to the location by H. erectus. On the

basis of this evidence, H. erectus was thought to be a hunter.

Figure 2.23. Comparison of choppers with chopping tools.

Reprinted, with permission, from Kelso, A. J. Physical anthropology.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.; 1970. [113]

Figure 2.23. Comparison of choppers with chopping tools.

Reprinted, with permission, from Kelso, A. J. Physical anthropology.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.; 1970. [113]

Table 2.12. Locations yielding evidence of Homo erectus.

|

Location

|

Date Found

|

Comment

|

|

1. Java

|

1890-91

|

Original discoveries of skull fragment and femur.

Originally designated as Pithecanthropus erectus.

|

| |

1936

|

Incomplete skull of an infant. Originally designated

H. modjokeriensis.

|

|

2. China

|

1937-39

|

Three incomplete skulls found about 40 miles (64

km.) from original 1890 discovery. Also identified as Pithecanthropus.

|

| |

1927-37

|

Several fragments of 15 skulls and 11 mandibles.

All were designated earlier as representative of Sinanthropus pekinensis.

|

| |

1949

|

A jaw bone, and five teeth that are similar to the

original 1927 find were found in the same deposits. A humerous and tibia

that can be attributed to modern humans were also found.

|

| |

1963-64

|

Mandible and skull fragments. Referred to as Lantian

man.

|

|

3. Germany

|

1907

|

A mandible, also called Heidelberg jaw and Homo heidelbergensis.

|

|

4. Algeria

|

1954-56

|

Fragments of three mandibles that have been designated

Atlanthropus mauritanicus.

|

|

5. Morocco

|

1954

|

From Sidi Abderrahman, a fragmentary mandible.

|

|

6. South Africa

|

1949

|

Some jaw fragments, teeth, and two bones of the postcranial

skeleton. Designated originally as Telanthropus capensis.

|

|

7. Tanzania

|

1960

|

Skull fragments referred to as Chellean man.

|

| |

1964

|

Identified by Leakey as "George," a skull reconstructed

from many small fragments.

|

| |

1976

|

Complete skull resembling Homo sapiens.

|

NOTE: Adapted, with permission, from Kelso, A. J. Physical

anthropology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.; 1970.

The evidence of H. erectus in Europe is meager. No artifacts

have been recovered in the sites where fossils were located. However, the

associated [114] fauna indicate that these beings may have lived during

the first interglacial period.

Artifacts discovered with the African H. erectus are indicative

of the advanced lower Paleolithic tradition. The Olduvai find in Tanzania

is associated with early hand ax archaeological remains. The H. erectus

fossil found near the bottom of Bed II is dated to one million years ago.

A recently unearthed cranium of H. erectus from Lake Ndutu in

northern Tanzania indicates a link between H. erectus and H.

sapiens. Both the cranial features of H. erectus and H. sapiens

are represented in this skull. It was dated at 500,000 to 600,000 years

by the amino acid racemization method. It is probably the transitional

form between H. erectus and H. sapiens (25,

26).

Collectively, H. erectus can be described as of moderate but

erect stature, as shown by the straight limb bones, broad hip bones, and

the position of the occipital condyle. The relative proportions of arms

and legs are like those of modern humans. The forehead is retreating, and

the jaw is projecting, though both to a much lesser extent than in the

ape. The dentition is essentially that of modern humans. H. erectus

was distributed throughout the Old World from about 1 million to 500,000

years ago, although not without exception (i.e., it has been claimed that

skulls buried merely 10,000 years ago in Australia showed typical H.

erectus characteristics) (27). They made the chopper-chopping

type or the hand-ax type of tool, both presumably having the same subsistence

function. Their appearance in the fossil record seems to be associated

with a shift of mammalian fauna toward a warmer and moister climate. H.

erectus was essentially a hunter and cave dweller, and at least at

one site found to date it appears he used fire for food preparation.

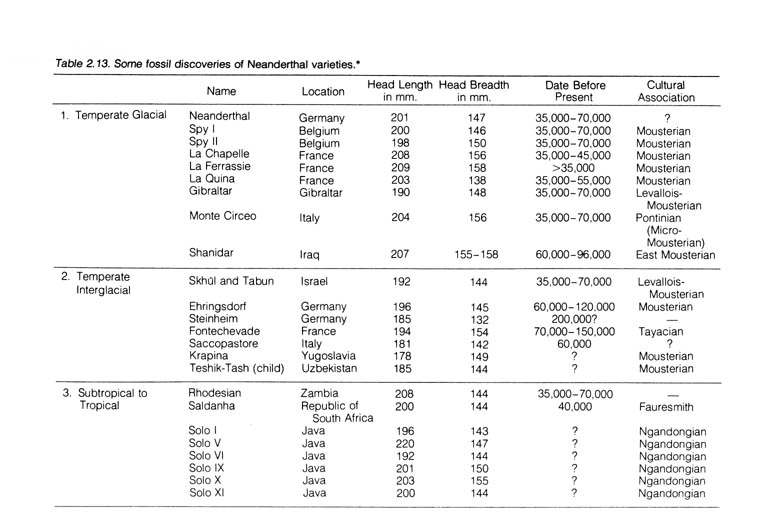

b) Homo Neanderthalensis Discussed. The first Neanderthal fossil

was discovered in 1848 at Gibraltar but was not thought to be significant

in the scientific community. Eight years later, a similar skull together

with a few ribs and limb bones were found in a cave in the Neanderthal

Valley of Germany. They were the first bones to draw the attention of anthropologists.

Since that time a large collection of similar fossils, some of them quite

complete; have been uncovered in the Republic of South Africa, Zambia,

France, Belgium, Italy, Yugoslavia, Israel, Uzbekistan, and Java (Table

2.13).

From the skeletal remains a rather complete picture of Neanderthal beings

can be constructed. Their skull was thick-boned, with prominent eyebrow

ridges and receding forehead. The roof of their skull was flat. However,

their average cranial capacity of 1450 cc exceeds that for some modern

humans (Figure 2.22). [115]

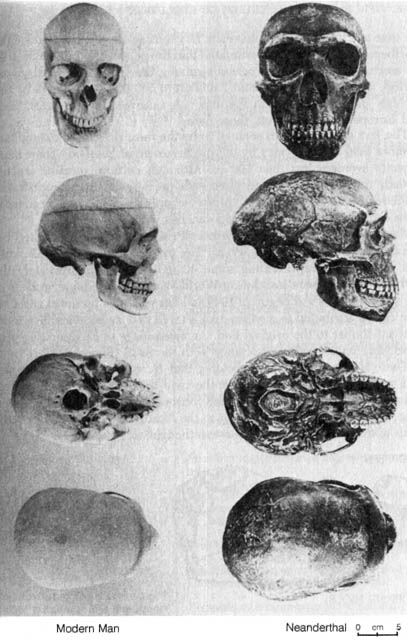

*NOTE: Reprinted, with permission, from Kelso,

A. J. Physical anthropology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.;

1970.

[116] The quality of the stone tools uncovered with the fossils

is indicative of middle to upper Paleolithic culture. Since they were scattered

through a period from approximately 150,000 years to 30,000 years ago,

they can be categorized into three groups according to the climates where

they lived: interglacial, glacial, and tropical. It can be safely concluded

that the glacial group of Neanderthal beings were hunters, whereas it seems

probable that the interglacial and the tropical groups were more vegetarians

than hunters. The interglacial groups were known to practice burials and

to place implements in the graves. The burials may have been in a single

grave, but multiple burials resembling a family cemetery were also uncovered.

A flint tool kit is frequently found buried with a dead male. One young

Neanderthal child was found buried with the horns of four ibexes, the great

mountain goat. The most impressive burial site was uncovered from the Shanidar

cave in the Zagros Mountains in northern Iraq. The skull of the burial

seemed to belong to a male around 30 years old who was killed by some strong

blows that badly crushed his head. He was buried on a bed with a blanket

made up of flowers, as evidenced by pollen analysis. This elaborate burial

rite leaves the impression that H. neanderthalensis believed in

life after death. It is also amazing to note that the man buried showed

evidence of a withered right arm that had been amputated, reattached, and

then healed.

Reconstruction from early finds depicted Neanderthal beings as persons

with a stooped posture. The discoveries of more Neanderthal remains changed

the picture. It is now apparent that the old conception of a Neanderthal

being had been based on a misinterpretation of the study of an arthritic

skeleton. Closer examination of the remains of other Neanderthal finds

suggests that H. neanderthalensis was not much taller than five

feet but stood with an upright posture.

Because of the advanced skeletal features of Neanderthal beings and

their advanced stone tools and burial rites, H. neanderthalensis has

been treated by many as a subspecies of modern humans — Homo sapiens

neanderthalensis. This interpretation was substantiated by the discovery

in caves of Mount Carmel in Israel of a possible intermediate between the

two species.

Since modern humans (Homo sapiens) appear abruptly at around

40,000 years ago at the advent of Upper Paleolithic culture when the Neanderthal

beings disappeared from Europe, it has been speculated that H. sapiens

neanderthalensis is the direct ancestor of modern humans. Except for

the recent find of a possible intermediate between H. erectus and

H.

Sapiens (21, 22), there is no

evidence against this interpretation. However, there are still unresolved

questions raised in several finds (e.g., [117] the Swanscombe skull and

the Steinheim and Ehringsdorf skulls) concerning the antiquity of H.

sapiens. Therefore, no conclusive human lineage can be established

to date.

However, it seems reasonable to assume that the earliest fossil that

can be placed in direct human lineage, according to the present evidence,

is H. erectus, who lived around 1 million to 500,000 years ago,

and possibly the KNM-ER-1470 skull. But the identity of this latter skull

has to await excavation of similar remains and, more importantly, the excavation

of cultural materials associated with this being so that the cultural capacity

of the fossil can be evaluated.

In summary, Ramapithecus and Australopithecus are thought

by many to be the ancestral stock of H. erectus. H. erectus is considered

by many to be the forerunner of H. Sapiens (modern humans). However,

the presence of conflicting interpretations of the fossil material and

the scarcity of cultural artifacts does not permit conclusive statements

to be made about the evolutionary position of these forms.

References 2.3

23. Bishop, W. W.; Miller, J. A., editors.

Calibration

of hominoid evolution: recent advances. Isotopic and other dating methods

applicable to the origin of man. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press;

1972: 177-85.

25. Mturi, A. A. Nature. 262:484; 1976.

26. Clark, R. J. Nature. 262:485; 1976.

27. Katz, S., editor. Biological anthropology.

15.